They moved hundreds of miles away, leaving behind the river and trees, green valleys and orange sunrises with streaks of pink. When she was eight years old, her parents packed all their belongings into boxes. People had never had money, they had always had homes instead, but they welcomed this change as an inevitability. Grown-ups talked about property value, and the mayor asked some people to sell their land and houses and move away. Likewise, when she bit them until they cried, they understood, too, and never showed their mothers the marks she left. She understood this, for she had known them their whole lives. Goba was taller and stronger than the other boys, so that they were obliged to bully her, too. She swore she would never take it off.Īfter Pasang left, Goba no longer had Pasang to impress, and his hatred of her intensified. It was just the kind of heart-shape she liked.

Pasang gave her a necklace, a gold heart on a chain. It seemed like an appropriate adventure for a Princess.

“Once I am a grown-up, I will come back here and marry you.” “Once I am sixteen,” she told Pasang beneath the purple tree, “I will come to find you.” Their parents said roads were being built all over the country, like the one which would soon allow them to get to the city. When she was six, and Pasang seven, the construction plans were finished, and Pasang’s father had to move away. Once, they kissed each other on the lips. They watched the grass shudder in the breeze and held each other’s hand. Sometimes they would sit beneath the purple tree, just so Goba wouldn’t see them. Goba had a tantrum every time he saw her. This infuriated Goba, who took it as a sign of Pasang’s affection. When her foot healed and she could play tag again, Pasang never chased her, though she was one of the smallest and the easiest to catch. Goba and his mother came too, with books and games, but Goba scowled at her and begged Pasang to play outside. Sometimes Pasang would come and draw beside her. When the older girls, and Goba and Pasang, came round to look at her swollen, bandaged foot, they looked at her with fascination and grudging respect. Goba’s mother found her and carried her home. When the door swung shut on her foot, she screamed so loud grown-ups came running. She was small for her age and half the size of the older girls. She picked the school’s heaviest door for the bruises. On her own, in case it hurt and she cried. The little girl tried it one day after school. She had never seen any of them shed a tear. One had to place a leg inside passageways and slam the door as hard as one could. These playtimes were interesting, but older girls were scary to copy. When Goba played with Pasang, she would follow the older girls around. He was spoilt and liked no one, except Pasang, who was the only one he did not consider beneath him. “See! See!” she cried, defiantly, determined not to be the first to give in. He wrapped his fingers around her neck and pressed, gently at first, and then harder, wondering how long she would resist. No one had killed her so far, she said, so it must be impossible for her to die. It was January, the air cold and smelling of the cookies his mother was baking. When he got out of the water, they both knew she had won. She took off her shoes, tied her dress around her shoulders, let the water sting her thighs. She dared him to go in, so he took off his shoes and dipped his toes in the icy water, his jaw clenched. One day in December, they went to the river together. Princes should never get too ahead of themselves, or of their Princesses. Naturally, she made sure he knew his place. She accepted it as the appropriate response. She imagined he did not know what love was.

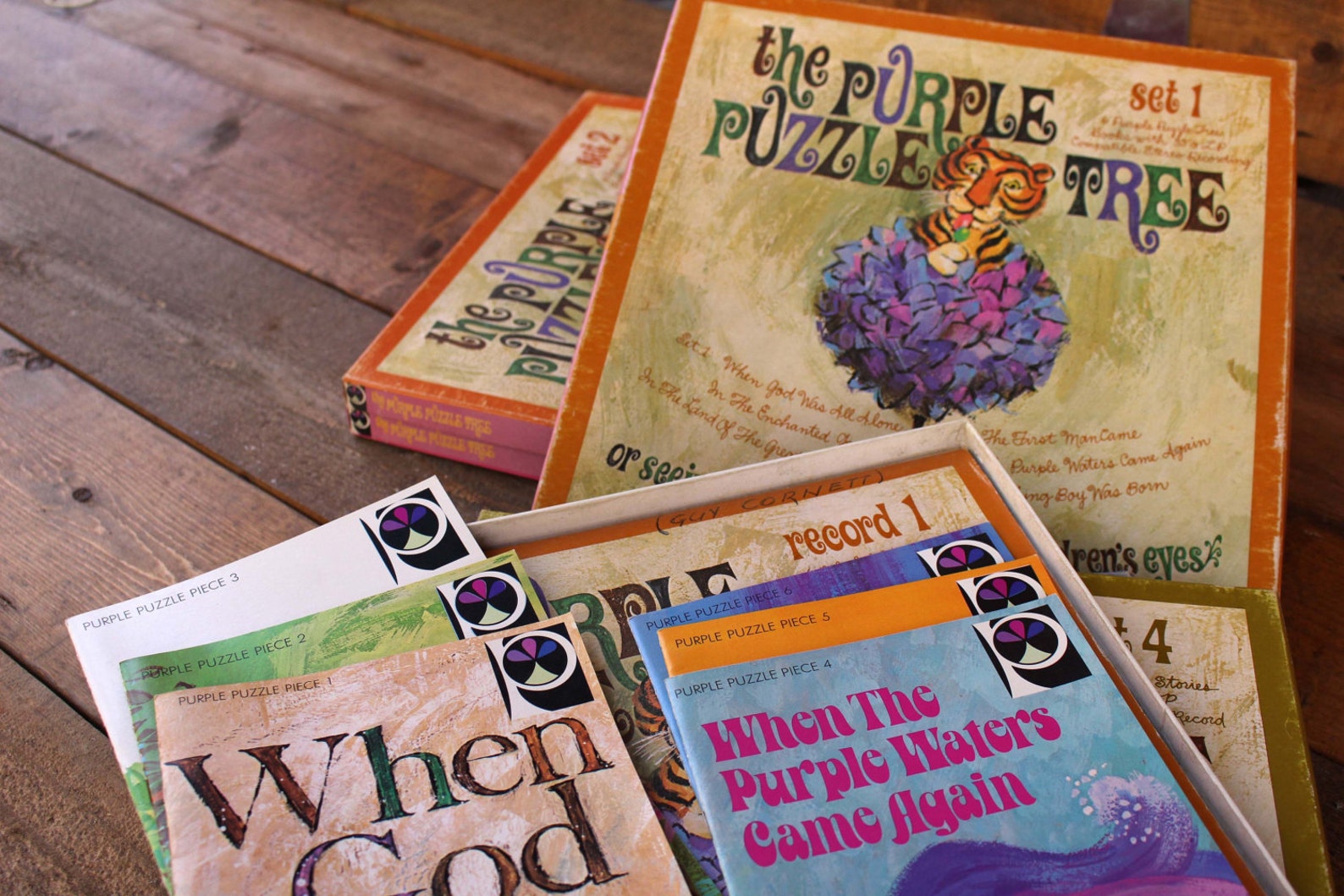

When she told Pasang she loved him, he blinked his large, quiet eyes. In the stories her mother told, all heroines had princes or pet bears. She decided that, should she ever need a prince, she would choose Pasang. When Pasang caught her, he did not pull her hair, or kick or slam her hard against the rough earth. Pasang joined in while his parents were still unpacking. It was the summer, when children roamed the furthest over the rolling hills. Those were the days, this was the place, where no one was excluded from village games. Even before she knew that people could use mouths for anything other than eating and drinking, she liked the look of it, its softness and slight downward turn. Pasang had a round face and a soft pink mouth. His father had come to work on construction plans. Pasang was the first and only newcomer the children ever knew. It was where, when she was four years old, she first saw Pasang. The tree was tall, its purple leaves like curtains, shielding its trunk.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)